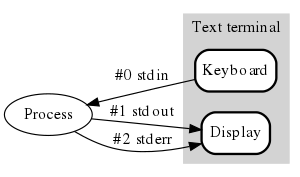

| A typical text terminal produces input and displays output and errors (Photo credit: Wikipedia) |

In Part 4 I managed to create a Hello World. What's the next program after this in every programming tutorial? A program that asks your name and greets you. Greeter perhaps?

Reading from standard input in pretty trivial, just wrapping up readLine function from scala, see previous post on how this is done. And I called this function readln.

Variables

I could cheat a bit and write something like thisprintln("who are you?")

println("hello", readln())

since I don't really have to store the name. This works but I also want to make a program that responds differently to different input, e.g. simplified authentication. So I want to store the input. Something like

print("enter passcode")

input = readln()

So I first create a case class to represent this

case class Assignment(to: Identifier, from: Expression) extends Expressionparsing isn't that hard either

private def assignment: Parser[Assignment] = identifier ~ "=" ~ expr ^^ {

case id ~ "=" ~ exp => Assignment(id, exp)

}

private def expr: Parser[Expression] = sum ||| assignment

Notice again my abuse of ||| where reverse order would have sufficed, don't do that.

Evaluation...here I had to make a choice. Where to put the assigned variables. In the same bucket as constants. Global variables ARE evil but I don't care since I'm having fun and I do it anyway. Don't worry this changes when I introduce function definitions and objects.

So StdLib became ScratRuntime and has a mutable map for storing values of identifiers. Full source here if you're interested. Of course some changes had to be made because of this refactoring. Full commit diff here.

Evaluation of assignment is now simple map put

case Assignment(name, exp) => {

val e = apply(exp)

runtime.identifiers.put(name.id, e)

e

}

The expression returns the assigned value so you can do a=b=1(in fact I didn't try that yet)What if

If expressions. I wasn't in the mood for parentheses or brackets so I went ruby style. Except my expressions are single line only(for now) so I had to put everything in one line. I needed a separator between the predicate and positive value and as an added bonus I didn't need the "end". So not much like ruby anymore but it was good inspiration.

I considered booleans but ultimately I can implement everything still in doubles(too much work to make whole type system of primitives when you can have just one type). Zero is False and everything else is True. So AND becomes * and OR becomes -. I'll add some equality so I can compare strings too.

I didn't need inequalities until now(didn't even think about before writing this post) so they aren't in the language yet.

Sample if expression

if input1*input2 then "okay" else "nooooooo"See, no parens. And I was inspired by scala to make the else part mandatory.

So how do I implement this? Case class is quite trivial, it has tree expressions: predicate, true value and false value. Evaluation just evaluates the predicate(recursion!!) and then evaluates and returns the appropriate expression

case IfThenElse(pred, then, els) => apply(pred) match {

case d: Double => if (d != 0) apply(then) else apply(els)

case other => throw new ScratInvalidTypeError("expected a number, got "

+ other)

}

That error is just a class that extends exception.

I added some more case classes and evaluation cases for Equals and NotEquals. They're very simple so I won't include them here(diff on github)

Parsing on the other hand is more interesting, here's the changed part.

private def ifThenElse: Parser[IfThenElse] =

"if" ~ expr ~ "then" ~ expr ~ "else" ~ expr ^^ {

case "if" ~ predicate ~ "then" ~ then ~ "else" ~ els => IfThenElse(predicate, then, els)

}

private def equality: Parser[Expression] =

noEqExpr ~ rep(("==" | "!=") ~ noEqExpr) ^^ {

case head ~ tail => {

var tree: Expression = head

tail.foreach {

case "==" ~ e => tree = Equals(tree, e)

case "!=" ~ e => tree = NotEquals(tree, e)

}

tree

}

}

private def noEqExpr: Parser[Expression] = sum ||| assignment ||| ifThenElse

private def expr = noEqExpr ||| equality

| layers (Photo credit: theilr) |

I finally got around to understand grammars a bit more. In order to make the grammar not ambiguous an not left recursive you stack layers upon layers. Like onion. And you use these layers to separate layers of precedence - most lightly binding operations being the upper layer(expr). This gets rid of ambiguity. And you can also use these layers to deal with recursion. Something in a deeper layer can contain an item from a higher layer - thus recursion - but it must first match something to avoid infinite recursion. And that's it. This is very well explained on compilers course on Coursera and I thought I understood the (very abstract) explanation but the evidence says I did not until I had some hands on experience.

A quick sample in scrat to finish it of

A quick sample in scrat to finish it of

print("enter passcode")

pass = "password"

state = if readln()==pass then "granted" else "denied"

println("access", state)

No comments:

Post a Comment